- Home

- Stephen McGann

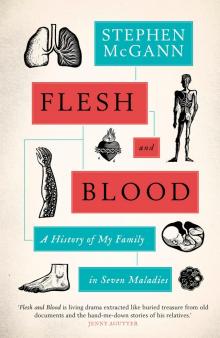

Flesh and Blood Page 14

Flesh and Blood Read online

Page 14

Her parents were delighted. My mum didn’t receive an engagement ring because of my father’s previous engagement to her sister. He didn’t think it seemly; part of an anxiety about public appearances that she’d later know too well. As the wedding day approached in September 1956, Clare became more hesitant and wanted to put it off for a while. Dad wouldn’t. The wedding dress had been borrowed, and the bridesmaids’ dresses had already been embellished by her sister Mary for the occasion.

My mum and dad were married on 29 September 1956 at St Anne’s church in Overbury Street, a short walk from the tenements where they lived. The service was at ten-thirty in the morning, which made for a long day. There was an afternoon reception back at the flat in Myrtle Gardens – then back to the Bay Horse Hotel for the evening revelries. Songs and pints and celebration.

Then the wedding night.

TESTIMONY

It’s the present day. I’m sitting in Mum’s cosy apartment in the beautiful city of Salisbury, nestling in the shadow of its glorious cathedral. My mother is now eighty-one years old; as fit and sharp as I’d ever wish to be at her age. In my own middle age I’ve grown to see the woman behind the mother who raised me – the forces that drove a quiet young girl to become the woman she was to all of her children. The traumas that shaped her. Clare Green is my friend, my inspiration, and the thread that holds my family to its past and present.

I ask her about the wedding night. My mum pauses. She takes a breath, searching for the right word to describe it:

It was … fraught. I didn’t know anything. I was expecting him to show me the ropes. He was an older man. A man of the world. But he didn’t have any technique – any way of being tender, or of making you feel loved. It wasn’t enjoyable.

My parents’ wedding night was a disaster. My father, for all of his years, service and bravery, was a virgin. He was a virgin racked by an anxiety that made physical affection difficult, and a mindset that couldn’t admit to the vulnerability it gave him. ‘He put his arm around me – but there were no words of reassurance. He probably felt pretty terrible himself. It was hard for both of us.’

It would be three weeks before my mother and father were able to consummate their marriage. Sex quickly became a trauma that buried shame like shrapnel deep into my father’s psyche. He suppressed the neurosis that it engendered beneath a carapace of outward propriety – retreating, wounded, into those rigid codes of gender that informed his undemonstrative childhood:

Sex became just a physical need for him. It wasn’t enjoyable. There was no real tenderness – no romance. When I expressed a need for more closeness he just said, ‘You’ve seen too many movies.’

Yet what my father lacked in tenderness and technique, he made up for in biological fertility. My mum became pregnant almost immediately. The newly-weds were living at Abraham and Mary’s flat at the time – and so my mum felt insulated from the full force of her new married life with Joe. The early pregnancy had an air of unreality about it:

When I missed my period I went to the doctor. He confirmed it, and then told me to come back at six months. No scans, no checks, nothing. Looking back, I should’ve been seen properly before then, but I didn’t know any better. It might have changed things.

As her pregnancy progressed through its early months, her bump grew unusually large. Her mother noticed it too, but there seemed little reason for alarm. By the end of the fifth month, her belly had grown so much that she could no longer sleep at night:

I couldn’t lie down because it was too uncomfortable. So I had to sit up in bed – and it got that way that I was disturbing your father’s sleep. So I started sleeping in an armchair at night.

After six nights in the chair, sleep deprivation began to take its toll. My mum was slurring words and barely conscious. The doctor was called. He felt her abdomen – it was now tight as a drum. She was sent to the maternity hospital with her mother.

When she arrived, she was referred for an X-ray, but before it could even be carried out, her waters broke in a huge torrent of amniotic fluid that soaked the bed. Mum’s eyes brim with compassion for the child she still was. ‘I was so naive. I actually turned to my mum at that point and said, “Does this mean I can go home now?” ’

She couldn’t. An X-ray confirmed twins, and she had now gone into labour. She was only twenty-six weeks pregnant.

The unexpected labour meant that she had to spend a seventh night without sleep, and accompanied by two nurses who still make her bristle with their coldness and indifference:

I hadn’t slept for a week. I was exhausted and scared. Every time I cried out or asked for help, they just tutted. They weren’t … compassionate. When the pains came I asked for pain relief. They refused, saying they didn’t want me to fall asleep. So I ended up with nothing for the pain. Instead, I’d count the tiles on the ceiling in the delivery room to take my mind off it … I’d see how many I could count before the next contraction …

When the babies finally came, the nurses called the doctor to cut her. The babies were small – just three pounds each – and she waited in the silence for their cries.

But the cries didn’t come.

I watch Mum’s face – the pain of it as fresh and raw today as it ever was: ‘I saw one of them. I saw his little leg moving in the incubator. It must have been John.’

The baby’s movement soon stopped. After an eternity, the nurse turned to her. She was brief and direct. ‘I’m sorry. Your babies died. They were too small.’

Two boys. One stillborn, the other hanging on for a few brief minutes. The little corpses were quickly whisked away. My mum never saw them again. ‘That was it. I didn’t touch them. I never got to hold them. I never even got to see their faces.’

Mum stared at the ceiling. The doctor stitched her up in silence. Then the nurse said: ‘Right. We’re going to take you to the post-natal ward to recover.’ It was a ward full of happy mothers and their newborn children. ‘I said, “No! Don’t put me with the babies! Please!” I must have made a hell of a fuss, because they put me back in pre-natal instead.’

The next day the doctor saw my mother and father in the ward. ‘These things happen,’ he said, briskly. ‘Just try again and come back next year.’ With that, he was gone. Mum and Dad were left alone to cope with it.

My mother spent the next ten days in hospital. It had been just eight months since her wedding day. In that short time all her hopes for future joy represented by her marriage and the new life inside of her had arrived stillborn, while the past certainties she’d known had been rudely whisked away without any opportunity to grieve. For the first few days she simply slept off her exhaustion. But then came the wound – the deep psychological trauma of it – spreading like sepsis inside her.

It must have been an awful time for my dad, too. While Mum was in hospital, he had to arrange the burial of his firstborn sons. In those days there were no special places in the graveyard for infants. There were no specific services in church. There was no counselling – even if he’d been the type of man to request it. He had to ask for permission to place his dead children in the coffin of someone recently deceased. His boys would be lodgers in death. The twins were sent to a public grave in Anfield Cemetery, and my dad cleared their flat of baby clothes.

We’d never know what it was truly like for him, because he never spoke of it. Ever. He never told my mother where the twins were buried, or what he’d arranged while she was in hospital. It wasn’t done as cruelty, but in the sincere belief that to address such pain was counterproductive weakness. He was doing what he’d always done. Burying pain and love and sensitivity beneath a straight-backed, stiff-lipped carapace. By the time Mum got home, everything was tidied away. There were sad ‘chin-up’ smiles, but the expectation was that she should now put it behind her. She was numb: ‘I wasn’t in floods of tears. I didn’t cry. I was … bewildered.’

At some level, Dad knew she wasn’t right. He took Mum on a week’s holiday to the Isle of Man. A

change of scene. Mum still has the black-and-white photographs. Smiling stoutly in the wind-blown sunshine, my young parents were united in a way they rarely were in future. She remembers it with fondness: ‘He was kind. Things were calmer. It was coming from a good place. Less fraught. Perhaps he needed to do it himself.’

However, when they got back from the holiday my dad made it clear that she had to move on. She was his wife and, pain or not, there were duties to fulfil. He found a rented flat for them nearby, so that she would now be removed from the childhood security of her family. She returned to her work at Littlewoods but Dad became more insistent that she give up work to look after him. My mum remembers the arguments – her nascent feminism seeded in the raw injustice of it:

I said, ‘Joe, before we got married you and I were the same – both working, both loving the same things – books, learning. But since then your life has stayed exactly the same and my life has changed completely! I had a life of my own but now you just want me to step into your mother’s shoes!’ And he replied, ‘Well, you’re married now. You’re my wife.’

As the summer progressed, the friction between them increased. My father’s anxiety and agitation became clearer to her once he was removed from the need to maintain a public calm in front of her parents. Sex remained ‘fraught’. By September, my mother could take no more. She went to see her doctor for a routine visit and burst into tears before she could even speak. Once started, the tears wouldn’t stop. The doctor was alarmed at her condition, and immediately called a psychiatrist colleague in a nearby hospital. The psychiatrist came to see my mother at ten o’clock that night while my father worked a late shift at the factory. He was concerned at what he found:

I was broken. So much had happened. I was trapped – I felt that nobody understood or cared. I didn’t know what to do with my life, I didn’t know which way to turn. I couldn’t even tell my mum and dad, because they wouldn’t have understood. I was trapped in this flat with a man who shut his mind down – retreated into doing his job, doing his duty, while I was supposed to get on with doing mine. I didn’t know what to do …

The psychiatrist’s response to the complexity of her pain was astonishingly blunt: ‘He said I was severely depressed. He told me that if I didn’t improve in three months, they would have to consider electric shock therapy.’

Electric shock therapy. In just a year my mother had been transformed from a healthy, intelligent young woman into a profoundly traumatised wife through a desperate lack of medical sensitivity and the emotional constipation of those nearest to her. Yet the only solution offered to this complex trauma was to fix electrodes to her head and throw the switch in the hope of improvement.

Electroconvulsive therapy is a procedure in which small electric currents are passed through the brain, intentionally triggering a seizure. How it works is still a mystery, but it can be very effective in certain cases. My anger lies not with its existence as a treatment, but in the idea that my mother was offered no defence against her life’s external antagonists beyond an induced seizure. The world’s traumas had left her in shock, but its only solution was to shock her further.

Yet she never did receive electroconvulsive therapy. I ask her why. Mum turns to me with a thin smile, ‘I got pregnant a month later.’

She became pregnant with my eldest brother Joe. An event, but not an answer. How did her depression lift? How did she manage to go on? ‘I just did what everyone wanted me to do. I got on with it.’

My mother gave in. She packed up her job at Littlewoods and stayed at home. She became a dutiful housewife. As my brother Joe grew inside her, she prepared her husband’s meals and washed his shirts. She took her trauma deep inside and kept it there. If she had to feel this alone, then she would do what she needed to in order to survive it. The person she’d been, and that woman she’d wanted to be, were now dead.

Except she wasn’t. Not by a long way. When my brother Joe was finally born, something wonderful happened. Something totally unexpected. My mum finally got to hold her own child in her arms and the effect on her was utterly life-changing. She still can’t speak of it without a burst of joy transforming her expression: ‘I became a mother. It was … amazing!’

She was totally surprised by her response to motherhood. My mum had never been particularly maternal – never longed to hold or tend to other people’s children. Yet as she stared into the clear blue of my big brother’s eyes, the clouds in her life were suddenly obliterated by sunlight – a reciprocated love that burned like fire in her veins. Everything became possible. Clare McGann embraced motherhood not simply with passion, but with a mission: ‘I wanted to be the best mother I could possibly be. I went straight out and I bought Dr Spock’s new book on childcare. I wanted to know everything about it!’

The months following Joe’s birth were probably the happiest in my parents’ marriage. The conformity my father required of his life in order to ease the anxieties he suppressed seemed finally to be in place. He was the Victorian patriarch with his own son and a wife who now conformed to her designated role as a stay-at-home mother. He was finally in control. The sounds of the beach were temporarily quelled.

Yet what my father took to be my mother’s compliance was simply unfinished business. My mum burned with a new purpose. Her children. She would go on to pour all of her love and fire into them, and in doing so would rekindle a desire for self-improvement and education that would ultimately take her beyond her husband’s control. Clare would ensure that her children’s characters were forged not in the dour frigidity of their dad’s upbringing but in the flexible courage of her own sensitivity. They would be a family of McGanns, but moulded in the image of Clare Green.

The happy days didn’t last. Eventually my father’s brooding depression and restless anxiety returned. He endlessly criticised my mum, finding fault with the smallest things. As Mum began to raise her new family, she learned to negotiate his black moods for the benefit of the children.

On one occasion, while visiting the family doctor, she decided to open up about it – and the doctor listened. At last, she found a physician who was sensitive to the psychological nuances she described. The doctor rooted out the medical file on her husband and showed it to her. It was there that Clare first saw the navy notepaper clipped into Joe’s file, and heard the term ‘anxiety neurosis’ for the first time:

The doctor said, ‘Your husband suffers from anxiety neurosis. This behaviour is due to his past experiences. He’s putting you down because it makes him feel better – more in control. In reality, your husband feels the pressure and responsibility of married life very heavily.’

This was a revelation to her. An answer at last. Her husband was suffering, damaged, kicking out like a wounded animal against the trauma and the pain he’d felt. He’d had a visit to a psychiatrist just after the war but had never told her, despite her own later depression. He’d kept everything hidden.

Clare was suddenly overwhelmed with compassion for her husband. She raced home to my dad and told him what the doctor had said. She offered suggestions for how she might help lift some of the stresses of his life from his shoulders, so that they could work together to fix it. My mother smiles and shakes her head at her naivety. ‘Of course he hit the roof. He was absolutely furious that the doctor had dared to reveal what was on his record. We never talked about it after that. Not ever.’

From that moment my mother and father followed divergent paths; together for many years to come, but increasingly estranged by their separate responses to their suffering. My mother learned to grow from the pains she endured. My father never could. Many years later and on his deathbed, my father took my mother by the hand and offered her the single acknowledgement that she’d spent a lifetime waiting to hear.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said.

‘It’s all right, Joe,’ she replied.

But it wasn’t. Not quite. Not yet. There was still something she had to do.

*

Following my d

ad’s death, my mum, now in her fifties, decided to become a bereavement counsellor. It was typical of her – turning her loss into a useful benefit for others. The training involved an induction course on various aspects of bereavement. On one particular night, the subject was neonatal death. ‘I was sitting listening to the counsellor talking about coping with the loss of an infant, when suddenly I began to cry uncontrollably. I just couldn’t stop.’

The counsellor took her to one side, and Mum tried to explain herself between sobs.

The twins. Her lost twins, all those years ago. With the mention of neonatal death, the pain of it had suddenly roared back into her mind like a blow to the head. She was overwhelmed by the force of it – the unresolved grief suddenly released from its long suppression by her husband’s death. ‘ “You’ve never grieved for them,” said the counsellor. “Nobody told me I could,” I replied.’

That night she couldn’t get the twins out of her mind. They were out there somewhere, huddled in an unknown grave. Lost. By morning she knew what she had to do. She had to find them. Call them by their names. Make them hers again.

Over the next weeks my mother did a remarkable thing. She set about finding her lost children. My father had told her nothing about the circumstances of their burial, so she had to rely on guesswork. She got lucky. She found the funeral directors my dad had most likely used back in the fifties. A friendly member of its staff took up her case and was able to confirm the stranger’s coffin that the twins had been placed into.

Weeks later, on a cold day in Liverpool’s Anfield Cemetery, my mother was taken by a grave attendant to the unmarked grave where her twins lay. They permitted her to place a small plaque of stone beside it. The plaque is inscribed with a simple quotation from the Book of Isaiah, chapter forty-two. It reads: ‘Know that I have never abandoned you; I have called you by your name; you are mine.’

Flesh and Blood

Flesh and Blood