- Home

- Stephen McGann

Flesh and Blood Page 18

Flesh and Blood Read online

Page 18

The drifting was over. The falling had begun.

TESTIMONY

‘Are you okay?’

My girlfriend is standing with her coat on in the living room of Birstall Road. She’s waiting for me to walk her to the bus stop. I’m not moving from my seat. I’m trying to control the agitation wriggling in my gut.

‘Fine. I’m just – tired. Hungover. D’you mind if I don’t walk you tonight?’

She looks at me. I feel the pulse beating in my ears as she watches me.

‘Sure. See you tomorrow.’

When she’s gone I feel my breath easing. The terrible dread that stalks me like a murderer from the window has withdrawn for now. The relief mingles with guilt at letting her go alone. My mind dispels the agitation it causes. It’s nothing. I’m not well, that’s all. A hangover. A cold. Fatigue. Something physical. Nameable. Easily explained. Nothing to be worried about. Nothing … else.

My mind can’t say it. It doesn’t possess the vocabulary. The names we give to things become the things we are. I can’t be that. My mind has been my mental strength in a life marked by physical weakness. It has consoled me through a bullied child’s tears and loneliness. It’s been my companion in solitude – the truth against which the fictions of my world were judged. It doesn’t lie, and it doesn’t judge itself.

I’m aware that the fear I have of stepping outside has no rational justification. The likelihood of sudden death is minimal. Yet the fear remains. It grins at the futility of my logic. Only in my house do I feel safe. Yet even here it haunts me. The terrible dreams at night. The permanent anxiety in my gut that I can’t shake. The dizzy unreality to my daily perception, like I was gazing at the world from behind dimpled glass. The slow asphyxiation of my future.

It’s 1982. I’m nineteen. I’ve been out of school and unemployed for a year, and housebound for a few months. Leaving the safety of my home, even for a quick visit to the shop, is an ordeal I must prepare for and one I rush to conclude. Yet I’m not diagnosed with anything. I haven’t seen a doctor and I haven’t acknowledged the facts of my condition. It doesn’t have a name.

Distant trips are the worst. To London, especially. I get nervous days in advance, and spend the whole time trying to control the panic that descends on me in crowded bars or theatre stalls. Paul is newly out of RADA and blazing a trail as a young actor. He’s appearing in a Trevor Griffiths play called Oi For England at the Royal Court. The family trek down to see him and we go for a meal afterwards. There’s a photograph of us smiling at the dinner table – grins and booze and family pride. Mark is there, now an actor himself. The clan are going places. The boys share a theatrical agent – a flamboyant and ambitious businesswoman who wants to unleash my family on an unsuspecting world. London has become a magnet for our dreams; a new destination for our cultural emigration.

When I look at my grin in that picture, all I remember is the pain it’s disguising. The crowded restaurant is suffocating me. I’ve developed a mask for my anxiety that gets me through the worst of it, but it’s exhausting to maintain. I’m longing to go home. At the same time I’m full of hate. I hate the merciless cruelty of it. I’m a hostile slave to its constraints. Running, not fighting.

It’s my girlfriend who first names it. She looks at me one night and says its name out loud.

‘I think you’ve got agoraphobia.’

I jump to my feet in agitation. The word ricochets around the tiny room in Birstall Road. I refute and scoff and deflect. After she’s gone I lie in bed, the room spinning. The word has come to life and reaches out to grab me in the darkness. I try to regulate my breathing. I try to remember those music lessons – breathing from my diaphragm, taking the air deep into the base of the lungs to loosen the tight muscles and shoulders. It’s no good. I’m still falling. Falling and falling and not waking up.

Then something stops me falling further. Anger. A white-hot furious anger, free of impurities. God, I’m angry! Angry at myself. Angry at the world. Angry at my weakness. It burns like potassium in the darkness. I’m furious at my agoraphobia. I can see the demon’s face in the potassium light. It’s the bully in the childhood playground who stole my lunch money. It’s the gang’s boot in my solar plexus. It’s the games teacher’s contemptuous grin in the school gymnasium. It’s the merciless asthma gripping my infant lungs, holding me back from my life’s potential. The oneline family biography, its blunt shorthand still suffocating.

The weakling. The one of whom too much must not be expected.

No. I’ve had enough. My mind has lied. Life has lied. I’m not this. I’m something better. I want to breathe. I want to be those full lungs of fearless air; the ecstatic suspension of breath when I make love; the diaphragm-powered courage of words delivered to the back of a packed auditorium. I want to sing a melody to which others can harmonise, to let the world hear all of the good and kind and strong things I can be. I don’t want to be agoraphobia. I want to be something else.

From that moment on there’s a new voice in my head. It startles me to my feet and drills me into positive action.

Get up, Stephen. Get up and fight.

*

Next to our house in Birstall Road is a small park over a covered reservoir. In the morning I walk down to the newsagent’s next to it and I purchase a newspaper. With every step I feel the bang of my heart in my ribs and the shallow, rapid fire of hyperventilated breathing. I wait in the queue with my coins in trembling hands. I take my newspaper and walk with deliberate care to the park. The sky lurches above me. The passers-by stare. I find a park bench and I sit. I breathe deeply to calm my heart rate. I take the newspaper and read the front page. All of it. Slowly. I steady my hands as the paper shakes. I read on. When the first page is done, I do the same with the second. Then the third. Garish headlines, advertisements, small-print gossip. Dog walkers pass my bench. Skipping children, their lungs clear, oblivious to my combat. Only when the whole paper is read do I allow myself to return home. I don’t run. I walk. Every step deliberate. Fighting for control. I get back to my house and I collapse on the bed, exhausted but resolute.

The next day I do the same. Then the next. Then the next. On and on until the knot in my stomach becomes a devil I know. An enemy territory I can reconnoitre without the blindness of shellshock. It’s a lonely melody sung without the expectation of harmony.

One day, my father arrives at the house. Mum must have said something – or else he identified something in my eyes that he recognised in himself. He tells me that he’s booked a private appointment with a specialist doctor in town. We travel there on the bus. Dad doesn’t discuss the appointment. He doesn’t say anything. The brittle worldview that he clings to doesn’t possess the vocabulary for shared fragility. He simply rubs my hair. The way he did when I had pneumonia. The doctor chats with me. I tell him about my drama interests. He tells me that it’s not unusual for people with artistic sensibilities to exhibit cognitive vulnerability. ‘It’s part of who you are,’ he says. An excess of reflection. Low self-image. He tells me I need to get out of my own head; take up a hobby, work with my hands. Have I considered sport?

He gives me a prescription for tranquillisers. My father and I leave the chemist’s without comment. On the bus home, the silence is painful. I long for Dad to tell me that he feels it too. I long to hear a single piece of wisdom that can help me complete the broken circuit of my thoughts. Make my life flow again, like the current in one of his old radios. Transmit my voice to the world. But he can’t. He can’t help solder the broken pieces of me together without admitting that he too rattles when shaken.

That night I take one of the little blue pills. The smog that descends on my brain is as suffocating as the anxiety I feel. A blunt instrument. I throw the pills away. I take a deep breath and return to my lonely melody unaided.

The summer passes in the park. Then, without warning, a moment of serendipity alights on my battlefield. Mark and Paul’s theatrical agent is throwing a party at a posh restaura

nt in London. It will be attended by the great and the good of London’s theatre scene. She hatches a plan to use it as a way to introduce London to her new protégés, the McGann brothers. She requires a band to provide the music for the night, and suggests that all four brothers do it. ‘Just to see what happens,’ she says.

The idea is terrifying. London. A strange room crammed with hostile eyes, watching me as I attempt to control the enemy in my head. Trying not to run. I hear the voice in my head again. Get up, Stephen. Get up and fight. I agree to do it.

That night in the restaurant, our band is truly terrible. Truly. We’re ill-rehearsed, out of tune and liberally sprinkled with strong drink. I try not to meet the eyes of the people I recognise from television as the amplifier feeds back over the party chattering. Eventually it’s over. I’m still alive. As I head to the bar to quieten the knot in my guts, a drunken theatre director blocks my path to tell me how great we were. I smile politely. He tells me that he wants all the brothers to be in a musical he’s doing at a theatre in east London. He’s slurring his words. I suggest he rings tomorrow. I watch him stumble away, and I shake my head. Tomorrow. He won’t remember his own name tomorrow.

Tomorrow. I wake on the sofa in my brother Joe’s London flat. I feel the tight, familiar intake of breath as I realise I’m not in my home bedroom. I breathe deeply to control the panic that builds. My head is banging from the booze. Joe’s telephone rings. It’s the director. He remembered. He was serious. He offers me a part in a musical with my brothers. I’m speechless.

‘I don’t have an Equity card,’ I tell him.

In those days, one couldn’t walk onto a professional stage in the United Kingdom unless one was a member of the actor’s union, Equity. A union card was almost impossible for an amateur to acquire. One or two were handed out each year by selected theatres to the lucky few.

‘I’ve got one to spare at my theatre,’ he replies. ‘D’you want it?’

For a moment I can’t reply. And then I do.

‘Yes – yes please.’

And that’s it. I’m a professional. A moment of serendipity has broken the long purgatory of my newspaper vigils and my stolen breath. A way to pick the lock and leave the dockside.

Maybe.

Will my anger be enough to propel me forward? Or will the mounting terror of what I’ve just agreed to do make me flee back to my home once and for all?

*

October 1982. The Half Moon Theatre, Mile End Road. A part of London’s thriving fringe theatre scene. The musical is called Yakety Yak – a glorious, foul-mouthed homage to the music of fifties songwriters Leiber & Stoller. I sleep on the couch at Joe’s flat and we take the tube to rehearsals. I breathe hard through the unscheduled stops in tunnels, squeezed tight against oblivious commuters.

Rehearsals are brilliant and scary and exhausting. We’re drilled by a choreographer – hour after hour until the weight drops off me like sweat. I can see my pale cheekbones and my hollow eyes in the bathroom mirror after nights spent drinking away the knot building in my belly as opening night draws near.

The theatre is very small. A few hundred seats at the most. There’s a reassuring cosiness to it. It feels like the youth theatre shows I did. If I squint my eyes I can convince myself that it’s not a very public place, and that my mounting terror can be deferred for a different battle. I can blend in – not be too exposed. Get it all over with. The boys are all crammed into a tiny dressing room together. It’s lovely. Like we were back in our old bunk-bedded room. The Four Musketeers. All for one and one for all. All of us bemused by where our lives have dropped us.

The first night passes and I survive. I don’t faint or die or run from the stage, despite the screaming in my head and the clawed breaths struggling to throw my constricted voice to the back of the tiny room. Surviving it feels thrilling. Fighting, not running. And something else. Barely detectable. A strength hiding inside the frailty, not yet brave enough to speak.

The audience goes crazy. Within days we’ve sold out the short run. The reviews are wild with praise. Hip magazines arrive to photograph us for glossy features. I see faces in the audience from television: newsreaders, alternative comedians, musicians. Columnists seek exclusives. For the first time since James McGann stood on the dockside in New York in 1912, the media has taken an interest in what my family has to say. I stand outside of it all – hiding in plain sight, not daring to believe that it can endure.

The demon is still my nightly visitor. It’s only the potassium anger that gets me through. A fury with life stronger than the weakness. Every day is exhausting. Like an extended trip to that park bench – newspaper in hand, reading every line and feeling every constricted breath. But I tell myself it’s not for ever. The run will soon end. I can return to the safety of home, my duty done.

Then, in the last week, the director calls a surprise meeting. He’s very excited.

‘Great news! We’re transferring to the West End!’

After just a few weeks’ break, we’re going to take the show to a huge new theatre. Hundreds more seats. The glare of new critics. A cavernous stage, looking out into impenetrable, lurching darkness.

Everybody cheers. My breath seizes in my chest.

I can’t. Not again. Not there. Not every single night for months and months. My anger won’t be enough. I need something else. Something more complete. A kinder voice. A deeper reason why. A better name for what I am. The strength that I can feel hiding inside my frailty. The thing my father can’t find the words for.

I need a better way to breathe.

*

January 1983. The Astoria Theatre, Charing Cross Road. The opening night of Yakety Yak.

The Tannoy in the dressing room picks up the expectant chatter of the audience. I’m in my costume and I’m staring into the mirror. Five minutes to go.

Four.

Three.

My stomach lurches. The breath catches in my throat.

My father is out there somewhere with my sister. He’s come to see his children unveiled to the wider world. He’s come to see a vindication for all of those years of duty and suffering. He’s come for an answer. I think about him at my age, running for his life in France. The courage of it. The fear of it.

Two minutes.

I think of him on that bus back from the doctor. Unable to share his own frailty with me. Unable to marry the courage in his life with the fear. His world brittle and mute. Me at his feet, listening out for some word of wisdom as he soldered in silence. Him like one of his broken radios, unable to transmit. A broken transistor, unable to integrate the impurities of his character into his own personality – the thing that every adult needs to do in order to turn the bricolage of childhood fears and needs into a flowing, flawed, complete, amplified human being, crackling with new life and singing their brave truth to the world.

One minute.

Then the penny drops. The simple wisdom delivered, unwittingly, all those years ago.

How transistors work.

How could I not have seen it? That gentle voice hiding beneath the cold purity of my anger and the breathless fear. The strength inside the frailty. The integration of my impurities into an amplified courage. A clean, strong melody funnelled through imperfect weakling lungs. The sound of my humanity breathing.

My brothers move around me in the crowded dressing room. Hands in mine. All for one and one for all. I watch their controlled nerves. I watch their private preparations. Now I see how each of them was drawn to the same career in the spotlight’s hard gaze. They did it to test their own lonely courage under strong lights. To gauge the nature of their strength and frailty by an exposure to strangers. To ask a question of life. To sing their own song in the hope of an answering harmony. To understand themselves in the absence of a key. To transmit. To breathe. To be a transistor.

Drama is human transmission. The communication of universal human vulnerabilities and strengths to others so that we might understand ourselves better. To

transmit those things you have to see yourself as all of yourself – the impure as well as the pure – the warrior as well as the weakling – the fear as well as the confidence. You have to integrate your own impurities as a human being into all of the strong things you are. You have to amplify yourself. You have to be a transistor.

‘Act One beginners please. Stephen McGann to the stage.’

I walk to the dim-lit stage. I hear the band preparing. I peep out through a hole in the set at the chattering audience. I see the faces of iconic pop stars and fearsome theatre critics. I think of Birstall Road, all those miles away. I feel the knot in my stomach tighten.

Yet I smile in spite of it.

‘Stand by.’

I am my agoraphobia, but it isn’t all of me. I am that asthmatic, but he isn’t all of me. I am so much more. I am humility, and courage, and shyness, and love, and the ecstatic breathlessness of climax. All of them necessary. All of them the things that make me into myself.

The names we give to things become the things we are. Yet I’m not my father. Instead, I’m one of his transistors. I can embrace the impurities that permit me to transmit the best of myself to the world.

The audience goes silent. I walk onto the stage and into the spotlight’s glare. I look out into the impenetrable, lurching darkness. I’m scared. But I’m not going to run any more.

I open my mouth. My diaphragm descends and air floods deep into my lungs. My chest muscles tighten to funnel the exhaled air towards the larynx. My vocal chords resonate. My throat and lips, tongue and jaw work in harmony to project words to the back of the theatre. I hear my first line. It’s clear and frail. Vulnerable and strong. A new skin. A new way to breathe.

*

* http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105160709/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/hsq/health-statistics-quarterly/no—18—summer-2003/twentieth-century-mortality-trends-in-england-and-wales.pdf

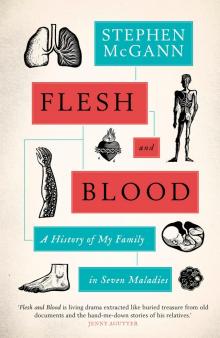

Flesh and Blood

Flesh and Blood